Communicating "Science" Through Art

As a visual communicator, I work to address the same concerns scientific and sustainability communities pursue in their field research and share through their data. I utilize immersive visual language to quickly introduce my research on far reaching issues of overfishing. A conclusion from the information shared may not be quickly garnered or universally accepted, but I believe the explorative presentations of my work support internal reflection on behalf of the active viewer. It further promotes the opportunity for communal discussion driven by the data fueling each piece.

100 Reasons

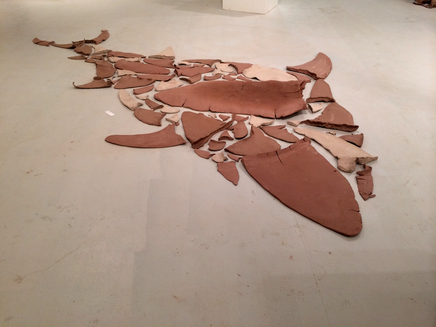

72 Sink

A way I explore bridging the two practices of science and art is by confronting the viewer with my collected creative research, and having the viewer tackle our own indirect participatory role of consuming fish. In 72 Sink, I play with my audience as a physical participant of my work, forcing them to confront a perspective commonly not considered. By having them inquire on shark finning’s negative ecological impact and economic drive, I create an encouraging opportunity for further discussion of the topic.

Referencing a world wide yearly average take of 72 million sharks, the 72 drying fin shaped clay forms visually represent the large quantity of sharks being removed in such a short time period. Foreshadowing an altered ecological balance, one has to confront the changes of the oceanic food sources we rely on.

Here, I compose a situation, where the potential of a participant breaking, moving, and kicking broken shards around the gallery space is allowed to take place and be observed. The intended result is a recorded reflection on how shark finning is just being walked over, even when the disturbing practice is distasteful to the viewer. By placing the fins on the gallery floor I adopt a visual component originating from my research, forcing the viewer to deal with the uncomfortable reality that “out of sight, out of mind” censoring is not a long term solution.

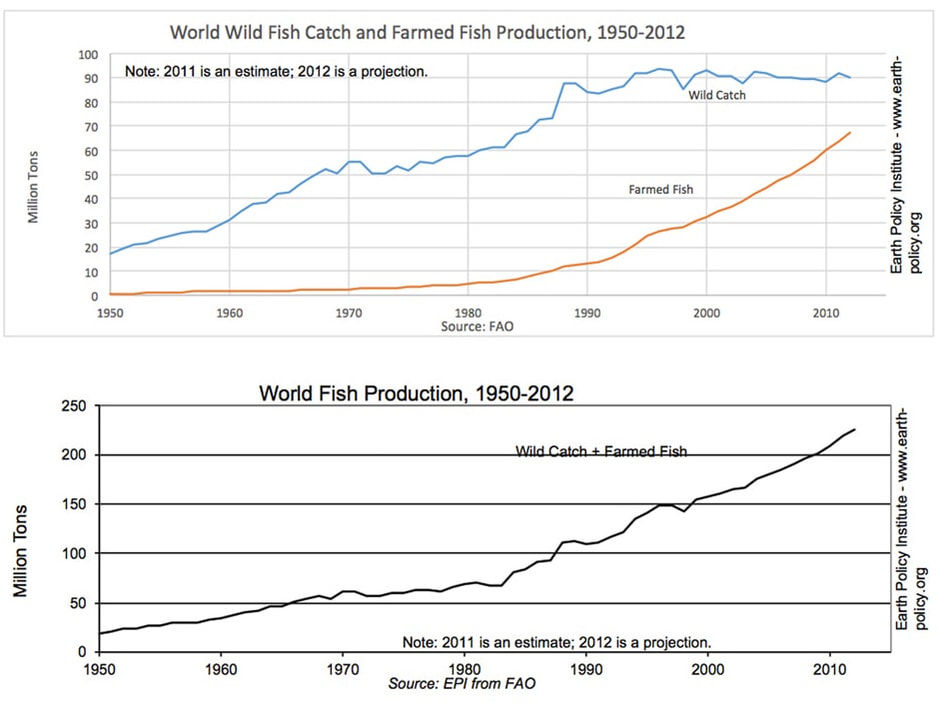

Catch 62

Catch 62 greets the viewer as an asymmetrical knitted wall and blankets the space with an engulfing warmth and familiarity. Its presence, however, embeds a secondary, harsh reality into the installation environment. The clues within the work slowly reveals a visual display of statistical data, cloaking 62 years worth of global commercial fishing and aquaculture statistics within its knotted design. Upon the realization from the participating viewer that the materials and colors employed are not meant to comfort and instead are presenting cold data on dramatic loss, Catch 62 creates a false read on one’s initial sensory experience. It becomes an uncomfortable, yet mesmerizing diagram of the growing demand we have put on the ocean—both in natural and artificial production—for sustaining our growing population and consumer demands.